Wastewater epidemiology isn’t a profession a script writer would likely give to a lead character in an action-adventure film.

In real life, however, experts in the emerging field may someday help protect and save more lives than a typical movie hero.

The Rockefeller Foundation, a supporter of ambitious efforts to promote “the well-being of humanity throughout the world,” is already convinced of the potential for wastewater research, monitoring and analysis to make our future healthier and safer.

The philanthropic organization has kicked off a major advocacy campaign to help trumpet a recent call from top researchers to bring the growing benefits of wastewater surveillance to all of the planet’s population.

In a recently published commentary in the research journal Nature Medicine the researchers explain how wastewater surveillance can aid the cause of public health. They describe how it can reveal the presence and track the accumulation and spread of pathogens — microorganisms like bacteria and viruses that can cause disease.

Among the authors are three Arizona State University researchers, Professor Rolf Halden and Assistant Professor Otakuye Conroy-Ben, both members of the faculty of the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, a part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at ASU, and Assistant Research Scientist Erin Driver with the Biodesign Center for Environmental Heath Engineering, directed by Halden, in ASU’s Biodesign Institute. Driver earned a doctoral degree in civil, environmental and sustainable engineering from the Fulton Schools.

Events leading up to the commentary and the advocacy push are reported in a news release from The Rockefeller Foundation emphasizing how wastewater surveillance has advanced as a science and can “provide a powerful early warning system for outbreaks” of diseases by detecting a range of viral and bacterial threats. That information can then enable public health officials to formulate effective responses to help quell those outbreaks.

Putting emphasis on preventative health care

In the release, a co-lead author of the Nature Medicine commentary, along with the director of The Rockefeller Foundation’s Pandemic Prevention Institute, say wastewater surveillance has proven its value during the COVID-19 pandemic and needs to be elevated to “a fully effective part of our public health arsenal.”

“If we can implement this more robustly and in more places around the world, we can do much better at protecting public health and avoiding the worst possible impacts of pandemics,” says Halden, who has been recognized for pioneering contributions to detecting the early warning signs of disease outbreaks and other dangers to the health of local communities in wastewater.

“By making wastewater monitoring a priority, we could discover the emergence of disease outbreaks faster than they become evident through the diagnosis of new patients going into hospitals and clinics,” Halden says. “This has been demonstrated recently in the outbreaks of the COVID-19 Omicron variant.”

Beyond early disease detection, Halden and his colleagues see the possibility of broadening our approach to health care by promoting a stronger focus on prevention. In other words, taking steps to make the public aware of what to do to prevent sickness and disease, rather than relying heavily on treating people after they become ill or contract diseases.

“Much of what we do in health care now is to play catch up, trying to heal people who are already in advanced stages of health problems,” Halden says.

He sees hope for reversing that trend as researchers continue to add to the hundreds of already discovered biomarkers — indicators of the condition of the body’s various biological functions.

“This is allowing us to detect and measure more kinds of potential and existing chemical, biological and physical threats to people’s health,” Halden says. “So, this presents significant opportunities for the ability of wastewater analysis to reveal problems in the very early stages.”

Accuracy in assessing health challenges

Driver’s work in Halden’s research center includes exploring applications of new tools and methodologies in health care and health science.

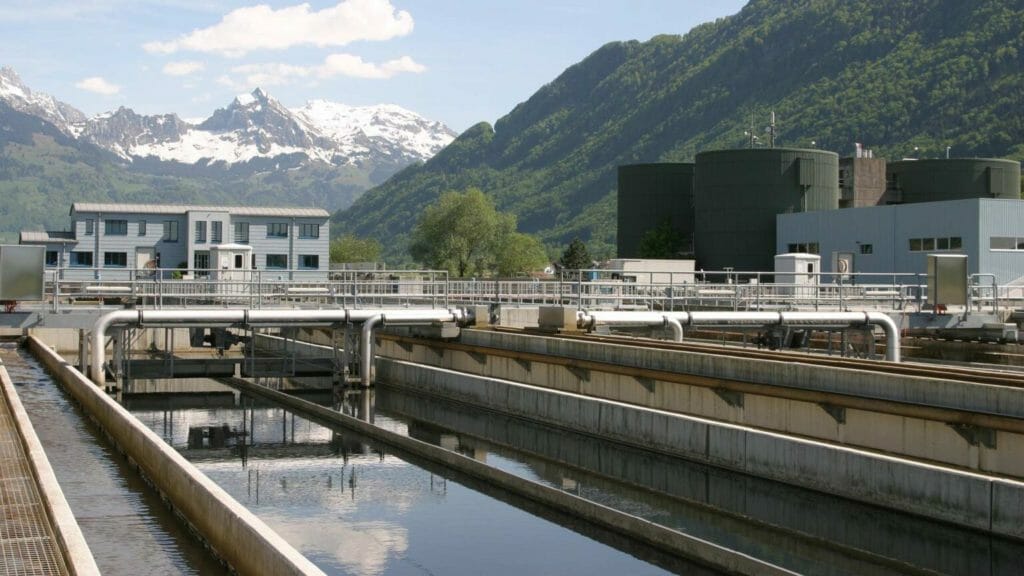

“One thing we are looking at doing even more is moving water monitoring beyond only wastewater treatment plants and into other places in communities,” Driver says. “That way we can make visible and track the success of interventions geared to particular health challenges among more specific and localized segments of a city’s population.”

Another of Driver’s goals is to learn from wastewater research what other kinds of technologies could be adapted or developed to provide environmental engineers with more accurate data relevant to their work.

“We’re looking for things that are easier to deploy and that provide the data and information we need more accurately and faster,” Driver says. “We need to make sure that all the various sampling and testing processes we use are giving us accurate pictures of the things we need to know.”

Removing threats to community well-being

Conroy-Ben, who teaches soil and groundwater remediation, and contaminant fate and transport, among related courses, concentrates her research efforts on water pollution and its biological effects.

“I’ve been studying wastewater for over 20 years, mainly focused on pollutant removal through various wastewater treatment processes,” Conroy-Ben says. “I look at the efficiency of removal of pollutants in wastewater treatment plants, including the removal of organic pollutants, endocrine disrupting chemicals, microbes, such as bacteria and viruses, and antibiotic resistant genes.”

With support from the National Institutes of Health, Conroy-Ben and collaborators Halden and Driver are bringing the scientific advances resulting from work in Halden’s lab in wastewater epidemiology to Native American tribal communities.

“Each tribe is different in various ways. So, I think what we learn from working with the tribes will lead to valuable insights into how to conduct health research in these diverse communities,” Conroy-Ben says. “I see a lot of progress being made as the tribes and other communities understand how discovering early signs of diseases and other health problems in wastewater can protect people’s lives by reducing harmful exposures.”

--

This story was originally posted on Full Circle. Read the story here.

By: Joe Kullman