Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute joins an international team led by the University of California San Diego School of Medicine to help unlock the causes of ulcerative colitis.

Researchers have identified microbiome-derived proteases in the gut contributing to the disorder, inspiring new potential drug targets for inflammatory bowel disease.

Ulcerative colitis, a subtype of inflammatory bowel disease, is a chronic ailment of the colon affecting nearly one million individuals in the United States. It is thought to be linked to disruptions in the gut microbiome — the bacteria and other microbes that live inside us — but no existing treatments actually target these microorganisms.

In a study published in the current issue of the journal Nature Microbiology, the group identified a class of microbial enzymes that drive ulcerative colitis, and have demonstrated a potential route for therapeutic intervention.

“Our study demonstrates a strong correlation between enzymes produced by a particular species of gut microbiota known as Bacteroides vulgatus and the initiation of inflammatory bowel disease,” said Qiyun Zhu, a researcher in the Biodesign Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics and ASU's School of Life Sciences. “We also shows that inhibiting B. vulgatus proteases may provide a new means of treating or preventing this disease.”

Although ongoing research has highlighted many correlations between gut health and constituents of the microbiome, such associations have, until now, shed little light on how bacteria cause diseases and how they may be treated. “This is the first study with experimental evidence that pinpoints a specific microbe driving ulcerative colitis, the protein class it expresses, and a promising solution,” said study co-senior author David J. Gonzalez, associate professor of pharmacology at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

The new research underscopres the power of so-called multi-omics — an approach that combines state-of-the-art genomics, proteomics, metabolomics and peptidomics to uncover the contents of a biological sample with unprecedented detail. The process of “digitizing” a sample allows the team to examine its biology at multiple scales and develop new hypotheses of disease progression.

“This study showcases the power of combining these technologies to explore biology in new ways,” said study co-senior author Rob Knight, PhD, professor and director of the Center for Microbiome Innovation at UC San Diego.

Studies of the gut microbiome often extract biological data from patient stool. The technique can provide a wealth of vital information and is far less invasive to collect than more traditional blood or tissue samples.

“Once we had all the technology to digitize the stool, the question was, is this going to tell us what’s happening in these patients? The answer turned out to be yes,” Gonzales says. “We’ve shown that stool samples can be extremely informative in guiding our understanding of disease. Digitizing fecal material is the future.”

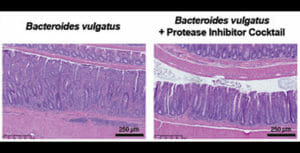

The team found that roughly 40 percent of ulcerative colitis patients show an overabundance of proteases — enzymes that break down other proteins — originating from the gut resident Bacteroides vulgatus. They then showed that transplanting high-protease feces from human patients into germ-free mice induced colitis in the animals. However, the colitis could be significantly reduced by treating the mice with protease inhibitors.

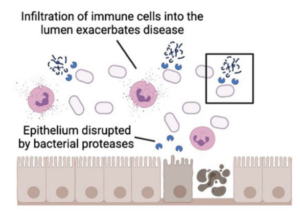

The team suggested that a stressor in the gut, such as nutrient deprivation, may increase protease production in an attempt to use proteins as an alternative nutrient source. However, these bacterial proteases may be damaging to the colonic epithelium or lining of the colon, allowing an influx of immune cells to then further exacerbate the disease.

Authors hope the study will inspire future work to confirm this hypothesis and develop protease-blocking drugs for use in humans. Now that a specific family of proteins has been implicated in this form of ulcerative colitis, they said, clinicians may also one day use antibody tests to quickly discern if a patient is a good candidate for protease treatment.

The researchers said their approach to stool analysis and multi-omic data integration might also be used to study other diseases, including diabetes, cancer, rheumatic and neurological conditions.

This research was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (grants P30 DK120515, T32 DK007202), the American Gastroenterology Association, and the Collaborative Center of Multiplexed Proteomics at UC San Diego.