By all appearances, the universe beyond Earth is a vast, lonely, and sterile space. Yet, wherever humans may travel, an abundance of microbial life will follow.

In a first study of its kind, lead author Jiseon Yang at the Arizona State University Biodesign Institute, Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics, and her colleagues characterized different bacterial populations isolated over time from potable (drinking) water from the International Space Station (ISS).

While historical monitoring of the ISS potable water system has focused on identifying microbial species that are present through both culture-dependent and independent (genome sequencing) methods, it is challenging for microbial identification approaches alone to faithfully predict the function of microbial communities. Understanding microbial function is critical to safeguard the integrity of mission-critical spacecraft life support systems and astronaut health.

The current study by Yang and her team investigated key functional properties of waterborne bacterial isolates from the ISS potable water system that were collected over the course of many years. The aim of this study was to expand our knowledge of how microbial characteristics that are important for astronaut health and space habitat integrity may change during long duration exposure to the microgravity environment of spaceflight. This is a critical issue to address, as microbial adaptations to microgravity been shown to dramatically alter bacterial characteristics, including their ability to form dense bacterial aggregates known as biofilms in the ISS potable water system that could threaten mission success.

Investigations of the function and behavior of mixed microbial populations are gaining traction in the scientific community, as these types of studies provide insight into how microorganisms interact with each other and their environment in practical settings. Such research can help provide crucial guidelines for the assessment of microbial risk to water systems in space as well as on Earth.

“Polymicrobial interactions are complex and may not be stable over time,” Yang says. “Our study provides in-depth phenotypic analyses of single- and multi-species bacterial isolates recovered from the ISS water system over multiple years to understand long-term microbial interactions and adaptation to the microgravity environment. The results from our study may improve microbial risk assessments of human-built environments in both space and on Earth”.

Yang is joined by ASU colleagues Jennifer Barrila, Olivia King and Cheryl Nickerson, who led the Biodesign team, as well as co-authors Robert JC McClean of Texas State University, and Mark Ott and Rebekah Bruce from the NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston.

The group’s findings appear in the current issue of the journal npj Biofilms and Microbiomes.

Life’s liquid

Water is a life-giving and indispensable substance, on Earth and in space. During spaceflight, a supply of clean water is essential for drinking and basic hygiene, but the challenges of reliably supplying it to astronauts are formidable, with every drop carefully managed.

According to NASA, without the ability to recycle water on the ISS, ~40,000 pounds of water per year would need to be transported from Earth to resupply just four crewmembers at an exorbitant cost for the full duration of their stay aboard the ISS.

The water purification system on the ISS, known as the Environmental Control and Life Support System, is used to cleanse wastewater in a three-step process. After initial filtration to remove particles and debris, the water passes through multi-filtration beds containing substances that remove organic and inorganic impurities. Finally, a catalytic oxidation reactor removes volatile organic compounds and kills microorganisms.

Although sophisticated life-support systems of this kind are designed to prevent contamination of this vital resource, bacterial communities have shown enormous resourcefulness in thwarting many preventive measures, with some forming biofilms throughout the ISS water recovery system.

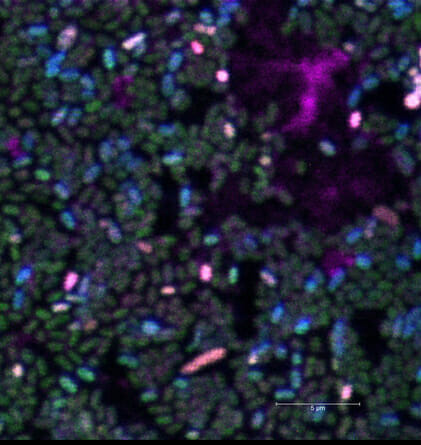

In the current study, microbial activity was examined in the NASA-archived bacterial isolates collected from the ISS potable water system over multiple years. Bacterial species were profiled for antibiotic resistance, biofilm structure and composition, metabolism, and hemolysis (ability to lyse red blood cells).

Tiny and determined

Despite the diminutive size of individual bacteria, which are unable to be seen by the naked eye, they are a force to be reckoned with. In addition to their individual abilities to cause a range of infectious diseases in humans, bacteria often clump together on surfaces to form dense multispecies aggregates known as biofilms, which are inherently resistant to being cleared by antimicrobials.

Bacterial biofilms have a major global socioeconomic impact and cause a myriad of health and industrial problems, resulting in annual economic losses in the billions of dollars on Earth. These problems include fouling oil and chemical process lines, encrusting invasive medical stents, causing infectious disease, and contaminating water resources. In addition, biofilms can also cause aggressive corrosion to a broad range of materials, including the capacity to degrade stainless steel, which is the material used in the ISS water system.

For these reasons, control of bacteria in complex microbial ecosystems and management of biofilm formation are vital challenges, made particularly acute during spaceflight.

Aboard the ISS, the NASA water recovery system continuously generates potable water from recycled urine, wastewater and condensation through distillation, filtrations, catalytic oxidation, and iodine treatment.

Despite these efforts, in-flight analysis of water samples from the ISS potable water system have shown microbial levels that exceed NASA specifications for potable water. The sources of this contamination are primarily due to environmental flora embedded in the water system itself.

Sky-high risk management

While many of the same microbes found in drinking water on Earth are also found in the ISS samples, there is a concern that the space environment may act to heighten the potential threats these organisms pose in this unique environment. Of particular interest are the conditions of microgravity, which members of this same research group have previously shown can enhance the virulence and stress resistance of some infectious microbes, alter their gene expression profiles, and encourage biofilm formation.

Compounding these issues is the fact that astronauts suffer aspects of immune suppression from spending time in the space environment, potentially leaving them more vulnerable to infection from microorganisms.

The results of the current study indicated that the ISS waterborne bacterial isolates exhibited resistance to multiple antimicrobial compounds, including antibiotics, as well as distinct patterns of biofilm formation and carbon utilization. In addition, one of the bacterial isolates, known as Burkholderia, displayed hemolytic activity, singling it out as a microbe of potential concern for astronaut health.

Observation of bacterial species interactions in this study also revealed distinct patterns of behavior, some of which were dependent on whether the samples were collected during the same year or over the course of different years, suggesting that adaptive processes were at work over time in the microgravity environment. Importantly, the dynamic phenotypes observed in this polymicrobial study would not have been fully predicted using sequencing technologies alone.

The findings from this study will help overcome the formidable challenges of ensuring safe drinking water for spaceflight missions, particularly those of longer duration. In addition, this study may provide information to improve the functionality of engineered water systems on Earth for industrial benefit and safety of the general public.

Jiseon Yang, Jennifer Barrila, Olivia King and Cheryl Nickerson are also researchers in the Biodesign Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics. Nickerson is a professor at ASU’s School of Life Sciences.