Over 170 million people in the U.S. are now fully vaccinated against COVID-19 -- more than half of the country's population. But as the virus evolves and new variants emerge, new questions follow. Are the vaccines effective against the delta variant? Will we need booster shots? What do we know so far about the vaccines' safety? We asked experts from Arizona State University to answer common questions and inoculate us against misinformation.

Why should I get vaccinated? [NEW]

1. The vaccine lowers your risk of catching COVID-19. Even though some vaccinated people do get breakthrough infections, they are far less common than infections among unvaccinated people.

2. If you do get sick, it won't be as bad. Vaccinated people who get infected almost always have a mild or asymptomatic case In Arizona, 99.5% of all people hospitalized for COVID-19 and 99.7% of people dying from COVID-19 were unvaccinated, as of Aug. 10.

3. The vaccines are safe, but getting COVID-19 isn't. Out of all the people who catch COVID-19: 1 in 5 ends up in the hospital, at least 1 in 10 experience long-term health problems, and 1 in 50 dies.

Still have questions? Want more details? Read on.

Do I have to pay for the COVID-19 vaccine? [NEW]

No. The COVID-19 vaccine is free to everyone living in the United States. You do not have to have health insurance. You do not need to be a U.S. citizen.

Where can I get the vaccine? [NEW]

You can find a free vaccine location near you through the Vaccine Finder website or by calling 1-800-232-0233 (TTY 1-888-720-7489).

ASU students, factuly and staff can sign up for free COVID-19 vaccines on campus through My Health Portal.

How do the COVID-19 vaccines work?

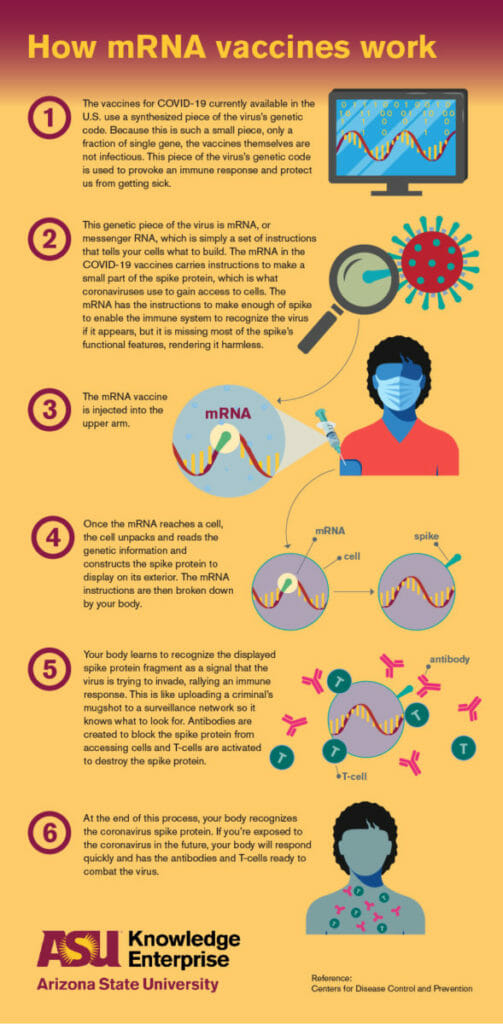

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is covered in a crown, or corona, of spike proteins that give coronaviruses their name. The viruses use these spike proteins like keys to get into human cells.

The vaccines train our immune systems to recognize these spike proteins and prepare to defend against them.

There are currently two types of COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use in the U.S. — adenovirus and messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines. Both types use the virus’s genetic instructions for building spike proteins to provoke an immune response.

The Johnson & Johnson shot contains a common virus called an adenovirus. This virus has been reprogrammed so that it can’t replicate or make you sick. Instead, it carries DNA with instructions for the coronavirus’s spike protein.

When your cells absorb the adenovirus, they copy the instructions for the spike protein into messenger RNA molecules. The cell uses this mRNA like a blueprint to start building spike proteins. The spike proteins make their way to the outside of the cell, where your immune system recognizes them as intruders and mobilizes an immune response.

The Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines work in a similar way, but they skip the adenovirus step. Instead of having your cells build the mRNA from DNA, these vaccines give you the mRNA directly.

In both types of vaccines, the genetic instructions are destroyed after use, like a self-destructing “Mission Impossible” message. However, the antibodies created by your immune system remain. If you’re exposed to the coronavirus in the future, your body will recognize the spike protein trying to access your cells and deploy antibodies in defense.

Learn more about how vaccines work to protect your body from ASU's Ask A Biologist.

How well are the vaccines working [UPDATED]

They are working extremely well.

"The intended benefit of the vaccines was to prevent serious illness and death. They are excellent at doing that," says Josh LaBaer, MD, executive director of the Biodesign Institute at Arziona State University.

Although the delta variant is causing more breakthrough infections among vaccinated people than before, the vaccines are still protecting against severe illness. In Arziona, for example, unvaccinated people make up 99.5% of COVID-19 hospitalizations and 99.7% of deaths.

“Far and away, all three vaccines are doing an excellent job at preventing hospitalizations and deaths. That's true everywhere, not just in Arizona,” LaBaer says.

Learn more about the delta variant.

Can I catch and spread COVID-19 if I am vaccinated [NEW]'

It's possible. Breakthrough infections -- cases of COVID-19 in vaccinated people -- are rare. However, there has been an increase in breakthrough infections from the delta variant. Delta is now the dominant form of the virus in the U.S.

"First, no vaccine is perfectg. We know that some percent of people don't mount as strong an immune response," says LaBaer.

However, there is another reason why the delta variant may be causing more breakthrough infections.

"One of the characteristics of delta is that it is better at elbowing all other variants out of the way," says LaBaer.

It does this by reproducing very quickly at the beginning of an infection -- possibly 1,000 times faster than other variants. This early period is also when people are most contagious.

Vaccines produce antibodies that fight the virus. Over time, the antibodies decrease, but our immune systems also have memory B cells that remember how to make them. When memory B cells are exposed to the virus, they start making more antibodies, but this can take a few days.

There is some evidence that people with breakthrough delta infections have high levels of virus at the start, before their B cells kick in and get the virus under control. That may be why vaccinated people tend to have mild cases -- their memory B cells churn out anitbodies before the infection gets out of control. But they could be contagious before this happens.

What are the side effects of the vaccine? [UPDATED]

Common side effects of the COVID-19 vaccines include fever, chills, fatigue, headache, and pain and swelling at the injection site. But those side effects are short-lived and not cause for concern.

“That's a great sign. Symptoms show that your body is creating an immune response to COVID,” says Heather Ross, a clinical assistant professor in ASU’s Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation and School for the Future of Innovation in Society. She participated in the Moderna vaccine clinical trial in summer 2020.

“After the first dose, my arm was pretty sore and I had a headache, but not anything serious. After my second dose, about eight hours after the shot I had a fever, I felt super tired and pretty grumpy for about 30 hours. And then I was fine,” she says.

“I do tell people, vaccination symptoms are a hell of a lot better than getting sick with COVID,” she says. “I have students, healthy young people, who are still getting short of breath when they try to exert themselves, months after recovering. It can be really, really disabling. We’ve seen people getting strokes after the fact from having COVID. It's really scary stuff.”

There have been some extremely rare, more severe side effects from the vaccines. These include allergic reactions, blood clots after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, and myocarditis and pericarditis in adolescents/young adults after the mRNA vaccines. Get up-to-date information about the reported side effects here.

It is important to remember that your risk of catching and dying from COVID-19 is far higher than the risk of any of these side effects.

Are there any long-term effects of COVID-19 vaccines? [NEW]

No. There are no known long-term effects from the COVID-19 vaccines used in the U.S.

More than 356 million doses have been given under the most intense safety monitoring in our country’s history. Anyone can report reactions through the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System. The CDC, Food and Drug Administration and other federal agencies investigate these reports thoroughly. They have not found any long-term problems caused by the COVID-19 vaccines.

This matches what we know about vaccines in general.

“The overwhelming majority of vaccine side effects show up within two months,” says Anna Muldoon, who holds a master’s degree in public health and is a PhD student in the School for the Future of Innovation and Society. “People don't get weird effects from a vaccine 10 years later. The body doesn't work like that.”

“I don't worry so much about long-term negative consequences, because we know they are really nonexistent in vaccines. And there's no reason to believe that this vaccine is going to be different from any others,” adds Bertram Jacobs, a professor of virology with the School of Life Sciences and a researcher in the Biodesign Center for Immunotherapy, Vaccines and Virotherapy.

On the other hand, COVID-19 is known to have serious, long-term health risks.

“Between 15% to 60% of people have long-term side effects of the virus, even people who had mild or asymptomatic infections,” says LaBaer. “Brain fog, memory problems, respiratory problems, gastrointestinal problems — these are showing up more and more. We now know in no uncertain terms that this virus gets into the brain.”

“If you’re worried about long-term side effects, there’s much more case for having them from the virus than from the vaccine. It’s naive to assume that when you get over the virus you’re done with it,” he adds.

How were the vaccines developed so quickly? [NEW]

It seems hard to believe that scientists could produce safe, effective COVID-19 vaccines faster than any other vaccine in history. But there are several reasons why it was possible this time around.

First, the scale of the crisis meant we had a global focus on creating a vaccine. Scientists, governments and private companies shifted their funding and effort toward a single goal, often through collaborative programs like Operation Warp Speed.

Second, vaccine developers took some steps at the same time instead of one after the other. For example, companies started manufacturing doses of vaccine before the clinical trials were finished. This is a financial risk they wouldn’t normally take. But it allowed them to start distributing vaccines as soon as the trials were successfully completed.

Another reason the vaccines could be developed so quickly is their underlying technology. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use messenger RNA (mRNA), which has been studied and worked on for decades. mRNA vaccines can also be made using readily available materials in laboratories. This means their production can be easily standardized and scaled, speeding up development.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine is also based on decades of research. The company previously produced an adenovirus-based Ebola vaccine, which was approved for general use by the European Commission in July 2020.

The widespread nature of COVID-19 also allowed scientists to quickly test their vaccines. To test a vaccine, researchers must give it to some people and not to others. Then they follow the two groups to see who gets sick and who doesn’t.

“Normally you might have to wait years and years for enough people in a clinical trial to get exposed to an illness, but because COVID-19 is so prevalent, particularly in the United States, we had many people getting sick with it,” says Ross. “We were able to reach those study goals much faster because so many people in the clinical trials did ultimately get exposed and get sick.”’

How do we know the COVID-19 vaccines are safe? [NEW]

Even though they were developed quickly, all of the vaccines underwent thorough clinical trials.

“In order to get the emergency use authorization, the manufacturer had to follow at least half the study participants for at least two months after completing their full vaccine series, which makes sure the vaccines are safe and effective,” says Jehn.

Combined, the clinical trials of the three vaccines included more than 110,000 people. All studies included men and women of all ages from a variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds.

“If you look at the ethnic makeup of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccine trial groups, they pretty closely mirror the ethnic makeup of the United States,” says Jacobs. “And that's actually pretty unique, because for many reasons, we've had difficulty enrolling minority communities in clinical trials.”

Worldwide, more than 4.72 billion vaccine doses have been delivered. Public health agencies around the globe continue to monitor people receiving the vaccines and investigate any reported effects.

ASU's Ask A Biologist explains how vaccines are tested.

Is natural herd immunity better than herd immunity by vaccination?

“Natural herd immunity” is a theoretical case of herd immunity achieved through naturally occurring infections rather than vaccines. But it may not even be possible.

“In recorded medicine, we have never reached herd immunity naturally. We have only achieved it via vaccination,” says Josh LaBaer, MD, executive director of ASU’s Biodesign Institute.

It would also be particularly difficult to achieve with COVID-19, because it’s unclear how long natural immunity against COVID-19 lasts after recovering from an infection.

“In this case, it's really good to have a vaccine in case natural immunity starts fading out,” says Muldoon.

Furthermore, herd immunity through vaccination will place less strain on our health care system and will ultimately save lives.

“Getting to ‘natural herd immunity’ means a whole lot of people are going to get sick and some are going to die,” says Ross. “And when we look at other diseases such as smallpox or polio, we would have never reached herd immunity without vaccination. What we would get is people with lifelong disabilities or who would die.”

What is the difference between an EUA and full FDA approval? [NEW]

On Aug. 23, 2021, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine received full approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Previously, all three COVID-19 vaccines available in the U.S. were granted Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs). An EUA allows health care providers to use medical products like vaccines during public health emergencies before they are fully approved.

To receive FDA approval, a vaccine must go through three phases of clinical trials. Phase 1 looks at the safety of the vaccine. Phase 2 ensures that the vaccine does what it is supposed to do. Phase 3 confirms both safety and effectiveness by studying much larger numbers of people.

To receive an EUA, a vaccine goes through the same three phases of clinical trials. At least half of the phase 3 subjects must be followed for at least two months after vaccination. In other words, vaccines that receive an EUA go through the same rigorous testing process that they do for FDA approval.

So what is the difference? First, full FDA approval requires more data. Fortunately, EUAs require manufacturers to continue monitoring the vaccines for safety and effectiveness, so they have been collecting that additional data all along.

Second, FDA approval involves many things not directly related to whether the vaccine itself works safely.

“They are not only clearing the treatment but also the instructions attached to it, the lot numbering process, the production process, the storage conditions needed, the packaging, all the things that we don’t even think about that attach to the drugs we take,” says LaBaer.

Should people who have had COVID-19 get the vaccine?

Yes. The CDC recommends that everyone be offered the vaccine, regardless of whether they have been infected.

“We think you have some sort of immunity if you were infected,” says Ross. “But we don't know how strong it is and we also don't know how long it lasts. So yes, we are recommending that even if you had COVID-19, you should still get vaccinated.”

This video from ASU's Ask A Biologist focuses on who should get a COVID-19 vaccine and why. (Video posted April 13, 2021)

Why did the CDC change its guidance for vaccinated people? [NEW]

Because the virus changed.

The delta variant is now the main form of the coronavirus in the U.S. It behaves differently than the original virus. Delta is infecting more vaccinated people, and there is evidence that those people can spread the virus.

Vaccinated people are not likely to get severely ill from COVID-19, even from the delta variant. But if they spread the virus to someone who isn’t vaccinated, that person could become very sick or die. Vaccinated people should wear masks around others to avoid passing along the virus.

Public health experts change their guidance when situations change, or when we learn new information. During a crisis like a pandemic, people need information quickly about a threat we don’t fully understand. We should expect that guidance will change as we learn more and should be prepared to check reliable sources of information regularly.

Learn more about coronavirus variants.

Do I need a booster shot? [NEW]

Not yet, unless you are immunocompromised.

The CDC now recommends a third dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna vaccine for immunocompromised people, such as those who have received an organ transplant. The FDA has authorized the use of extra shots in this group.

The Biden administration recently announced a plan for offering booster shots to people depending upon when they received their vaccine doses, based on new evidence that the vaccines lose some effectiveness over time. The FDA and the CDC’s independent advisory committee are currently reviewing the evidence to authorize the boosters and make recommendations for their use. Once authorized, boosters could be available as soon as late September. Those at highest risk, such as nursing home residents and health care workers, would receive boosters first under this plan.

Should I still get tested after I get vaccinated?

Yes, if you have symptoms or have been exposed to someone who tested positive. Vaccination is not a golden ticket to never worry about the coronavirus again.

“People can still get infected, which means they can still carry the virus,” says LaBaer. “And until we get a greater proportion of our population vaccinated, testing is a way of making sure people aren't asymptomatically carrying the virus.”

LaBaer, who has been vaccinated, gets tested when the situation calls for it.

“If I'm going to be near somebody who hasn't been vaccinated, or I travel, or I’m heading to an in-person meeting, I'll get tested,” he says.

ASU offers free, saliva-based PCR testing on all campuses and throughout Arizona. Find a free COVID-19 test near you.

Is natural herd immunity better than herd immunity by vaccination?

No, and it’s probably not even possible.

People become immune to diseases by getting vaccinated or by getting infected. “Herd immunity” means that so many people are immune that the disease can’t continue spreading. Herd immunity is important because not everyone can get every vaccine, such as people with suppressed immune systems or babies who are too young.

“It's very possible that there might be someone in your life who can't get vaccinated,” says Muldoon. “So, the more people get vaccinated, the more we can protect those people in our friend groups and families.”

“Natural herd immunity” is a theoretical case of herd immunity achieved through infections rather than vaccines. But it may not even be possible.

“In recorded medicine, we have never reached herd immunity naturally. We have only achieved it via vaccination,” says LaBaer.

It would also be particularly difficult to achieve with COVID-19, because it’s unclear how long natural immunity against COVID-19 lasts after recovering from an infection.

“In this case, it's really good to have a vaccine in case natural immunity starts fading out,” says Muldoon.

Furthermore, herd immunity through vaccination will place less strain on our health care system and will ultimately save lives.

“Getting to ‘natural herd immunity’ means a whole lot of people are going to get sick and some are going to die,” says Ross. “And when we look at other diseases such as smallpox or polio, we would have never reached herd immunity without vaccination. What we would get is people with lifelong disabilities or who would die.”

What is in the COVID-19 vaccines?

The Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines contain messenger RNA (mRNA), lipids and saline solutions. The single active ingredient — mRNA — is contained within a protective bubble of lipids. The saline solutions in the two vaccines are commonly used in medications and vaccines and serve to keep the pH and salt levels of the mixture close to those in the human body. Both vaccines are essentially genetic material wrapped in a bubble of fat suspended in salt water.

The full ingredients of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine are: messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), four lipids: SM-102; polyethylene glycol (PEG) 2000 dimyristoyl glycerol (DMG); cholesterol; 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC); and the saline solutions comprised of tromethamine, tromethamine hydrochloride, acetic acid, sodium acetate, and sucrose.

The full ingredients of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine are: messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), four lipids: (4-hydroxybutyl)azanediyl)bis(hexane-6,1-diyl)bis(2-hexyldecanoate); 2-[(polyethylene glycol)-2000]-N,N-ditetradecylacetamide; 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and cholesterol; and a saline solution of potassium chloride, monobasic potassium phosphate, sodium chloride, dibasic sodium phosphate dihydrate, and sucrose.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine contains a modified adenovirus with coronavirus DNA, as well as various stabilizers, alcohol for sterilization, an anticoagulant, an emulsifier to hold the ingredients together and salt.

The full ingredients of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are: recombinant, replication-incompetent adenovirus type 26 expressing the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, citric acid monohydrate, trisodium citrate dihydrate, ethanol, 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HBCD), polysorbate-80 and sodium chloride.

Do the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines change your DNA?

“No, absolutely not,” says Jacobs.

While Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines contain genetic material (mRNA), they have no effect on our DNA. These messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines simply deliver instructions to our cells to make a single protein from the coronavirus. Once the protein is created, those instructions are broken down and the protein piece is displayed on the surface of a cell. Our immune systems recognize that it doesn’t belong and make antibodies in defense. This is the same way our bodies respond to a natural infection.

“DNA is like a very big blueprint, let’s say 20,000 pages long. If you want to make something on page 1,000, you don’t take the whole blueprint to a factory. Instead, you make a photocopy of that page,” says Jacobs. “Then, once the factory starts making what’s on the photocopy, it’s torn up so they can start making whatever else needs to be made.”

That’s messenger RNA, says Jacobs. The mRNA does not remain in the body. It’s disposed of once it delivers its instructions and does not impact our DNA.

Heather Ross is a nurse practitioner and holds a doctorate of nursing practice and PhD in human and social dimensions of science and technology. She currently serves as a special advisor to Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego.

Anna Muldoon previously worked in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the Department of Health and Human Services as a science policy advisor. She currently works in Biodesign’s Modeling Emerging Threats for Arizona (METAz) Workgroup and recently co-authored COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories: QAnon, 5G, the New World Order and Other Viral Ideas.

Bertram Jacobs has been working with vaccines for more than 25 years and is one of the world’s foremost experts on a poxvirus called vaccinia, a cousin of the smallpox virus. He has genetically engineered the virus as a vehicle against numerous infectious agents, bioterrorism threats, cancer and other viruses, including HIV.

Megan Jehn received her doctorate and master's of health science degrees from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health in clinical epidemiology. She played an integral role in Maricopa County’s Serosurvey and is a member of the Arizona CoVHORT, a collaboration between public health and medical researchers to examine COVID-19’s effects on Arizona.

In addition to leading the Biodesign Institute, Josh LaBaer is director of the Biodesign Virginia G. Piper Center for Personalized Diagnostics. He is an expert on using biomarkers — unique molecular signifiers of disease — as early warning signs of diseases like diabetes and cancer.

Written by: Peter Zrioka and Diane Boudreau

Read the original article posted January 19 on ASU Now.

This site (story) reflects current public health guidance and is subject to change throughout the spring semester, and ASU will continue to proactively communicate changes as they arise.

This article was updated on August 23, 2021.