I remember it like it was yesterday. I was 14. My mom and dad sat me down at the kitchen table and said, “Look, this is going to be a challenge. Your mother has terminal cancer.” It was a stunner. My mom was 44 years old.

Suddenly, the carefree days of riding my bike, playing non-stop basketball and hanging out at the gym were over. Now I spent my time trying to comprehend cancer, monitoring my mom’s illness and taking turns with my dad and my sister, flying mom from Allentown, Pennsylvania, to the Bethesda campus of the National Institutes of Health. Dorothy LaCava, the state’s first special education teacher, was now a medical guinea pig. Despite the many challenges, she participated willingly for three years because she so desperately wanted to live.

It was the mid-70s, and medicine didn’t have much to offer. For people with cancer, it was essentially chemo or radiation — neither of which were pleasant alternatives. As I wheeled my mom through Washington National Airport, I witnessed the toll the heavy chemo sessions were taking on her body and spirit. I think it was then that I began thinking, “This has to change.”

She honored her promise to stay alive until I graduated from high school. My mom lost her courageous battle with breast cancer when she was 49 years old.

#1: Play to your strengths

The real tipping point came just a few years ago when my wife’s closest friend, Dede, died from pancreatic cancer. We walked with her through her struggles for a year, but like my mother, Dede died when she was 49, leaving two children behind. I felt like it was in a replay. The diagnostics and treatments were entirely too familiar.

Now I was angry. Why aren't we — after all these decades — doing a better job of treating cancer? Why wasn’t Dede diagnosed earlier? Why were we using nearly the same medical techniques we used 40 years ago? What's the problem here?

That's when it was time to get in the battle and do something. When you are affected by cancer, whether it’s a relative or a friend, you feel helpless. My sister, Sandy, my wife, Jill, and I said, “Let's take our best shot at trying to make a difference.”

That's when we decided to start The Dorothy Foundation. That was the key. We knew we were novices, newbies, but we felt if we don't do something, shame on us.

At the Dorothy Foundation, we have two goals. One, find ways to make information about cancer research more readily available to researchers, physicians and patients. There’s a gold mine of knowledge out there, but it can be disconnected and difficult to find. Modern tools of communication are helping us open that door. Second, we want to support the most promising and innovative research in the field.

We didn’t have a lot of money to start; certainly not the millions you hear about in the world of philanthropy, but we had passion and perspective. I knew I could use my connections and my platform as a TV personality to bring attention to the problem. So the adventure began. We’re learning as we’re doing.

#2: Work with the home-run hitters

When I met Dr. Josh LaBaer, we had an instant connection. Like me, Josh lost his mother to breast cancer. But we had one major difference — by the time his mother was diagnosed, Josh was an internationally recognized cancer researcher. The striking similarity was that he felt nearly as helpless as I did in our desire to spare our moms from suffering. Josh’s experience with his Mother clearly etched in him a fierce commitment to finding answers for cancer faster.

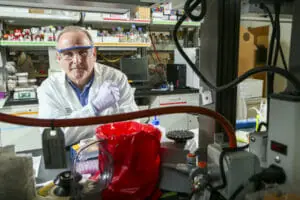

Our first Dorothy Foundation investment was to Dr. LaBaer at ASU’s Biodesign Institute. This was a seminal period is his research, when our relatively modest donation of $10,000 allowed him purchase samples he needed to move his research forward. Josh was looking for a way to diagnose breast cancer for the many women for whom imaging doesn’t provide a clear enough picture. Today, Josh’s diagnostic, Videssa Breast, is on the market and helping make breast cancer diagnoses earlier, more accurate and easier.

Another opportunity grew from my friendship with executives at a local beverage distributor, Breakthru Beverage. They were directing funds they raised at their annual charity golf tournament to various local charities. Hoping they would see some merit in providing a gift to cancer research, I told them about the Biodesign Institute.

Most of them were surprised that such an organization even existed. I arranged a tour and a chance for them to get acquainted with some of the researchers. They were blown away by the energy, expertise and possibilities. We learned that Arizona has among the highest rates of skin cancer in the world. It was a perfect opportunity to educate golfers about cancer risks, while convincing them to get involved in the fight. Together with Breakthru Beverage, we provided a gift of $25,000 to advance melanoma research at Dr. Stephen Albert Johnston’s Innovations in Medicine Center at the Biodesign Institute. The gift helped Dr, Johnston purchase the blood samples he needed to move his work forward.

Our early investment in Dr. Johnston’s work has resulted in the development of a non-invasive diagnostic platform that can detect 90 different diseases with one drop of blood. Now, U.S. government agencies are working with Johnston’s lab because they see strong potential for using this simple and inexpensive test in the field. Soon, Dr. Johnston’s test for diagnosing cancer early will be available to physicians and patients through his startup company, Calviri.

#3: Rely on your relationships

Friendships grow one-by-one. A friend and colleague struggled through the pain of losing his wife to advanced melanoma. I was privileged to walk with him through some of his ups and downs. As he struggled to accept her death, it was clear that one of his needs was to take action, to help others.

He himself wasn’t in a position to contribute, but he knew people who were. During one of our talks, he mentioned he had a friend who had become successful by building senior centers around the world, a friend who had a natural penchant for generosity.

He told his friend about the work happening at the Biodesign Institute and we invited him to meet some of the researchers to learn more about what they were doing. The researchers were enthusiastic about answering our guest’s many questions. By the end of our day at Biodesign, he was eager to make a significant donation.

That's how you broker relationships. What was good about this experience is that it wasn't your standard fundraising campaign. It was more like “let's sit for a couple hours and let's learn from the experts.”

#4: Don’t be afraid of the ‘valley of death'

The “valley of death” is what researchers call the period between when they receive funding from traditional science funders and the funders that will help bring their discoveries to market. This is a time when funding sources are scarce. It’s also the graveyard where good ideas go to die. A lot of research takes 10 years, 20 years — even 30 years before it is available to the public. Some funders are impatient and want to fund during the “big bang” period. Small private gifts during the developmental stages can make an enormous difference; keeping those ideas alive so the discoveries can help humankind.

Most of us are far more aware and attracted to organizations that deliver the discoveries at the patient’s bedside. We are influenced by the emotional tug of solicitations that show doctors and patients. But without the discovery-driven research that happens in places like the Biodesign Institute, many of those technologies and treatments would not exist. While the scientists in research labs are often cloistered behind closed doors — and not at the patient’s bedside — they are no less caring and motivated to deliver solutions that will improve the health and wellbeing of people.

#5: Understand that information saves lives

Ask me how a sports journalist saved a life. To meet our goal of making cancer research information more widely available, we identified a brilliant man who is using the new tools of technology to create a “go-to” database called the Cancer Commons. Do you know how hard it is for people to find information about clinical trials? Well, Marty Tenenbaum is working relentlessly to change that.

One of my friends was battling non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. She was about my age, full of life, with a successful career and a beautiful family. Her medical options were limited, and she didn’t know where to turn.

I told her about the Cancer Commons and encouraged her to check it out. Through Cancer Commons, she learned about a clinical trial happening in her own backyard. She participated in the trial, benefitting from a new form of immunotherapy. Today, she is cancer-free and recently experienced the joy of walking her daughter down the aisle.

Did I save her life? Well, no, not really. But you can imagine the personal satisfaction I felt by helping her make the connections that saved her life?

It’s time to celebrate our scientists

As a sports reporter, I live in the world of games. Covering sports contests is like covering the toybox of life. But my real passion is in life itself. How can we become active players in this game called life? For me, it’s time to focus on the promise of science. As a society, we enthusiastically celebrate athletes and celebrities for the fun they bring to our lives. We place them on pedestals and under the spotlight. The people who truly deserve this kind of adulation are our real superstars. Hardworking. Determined. Hidden. Scientists.

I have a vision that someday soon someone will create a half-time show where we put our scientists on the 50-yard-line and celebrate the many lives they have saved — and the many they have yet to save.

Our greatest victory is yet to come. We need you to join Team Science.