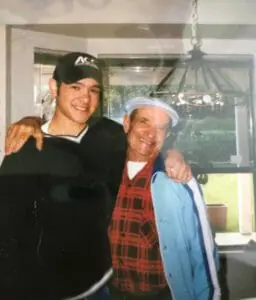

“My mother was driving to work one morning and was alarmed to see an older man riding a bicycle against traffic,” says Diego Mastroeni. To her surprise, that man was his grandfather, Giuseppe Abramo. For Mastroeni, now an assistant research professor and neuroscientist at Arizona State University’s ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center, dementia struck close to home, with painful immediacy.

Mastroeni has warm memories of teaching his grandfather to speak English and spending magical hours gardening together at his home in Italy.

Abramo was a veteran of World War II. He had seen firsthand the horrors of war. As he aged, sounds, sights, even smells, would trigger sporadic, surprising and even violent reactions. Mastroeni was 16 when his parents asked him to take his grandfather to the dementia care facility, for Abramo trusted only him.

“This was the defining day when I changed from a boy to a young man,” Mastroeni says. “As I held his hand as he had held mine all those years, I promised I would be back to visit.”

Fast-forward 25 years, Mastroeni, his wife and two daughters live in the United States. His 85-year-old grandmother-in-law is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, and must leave the ranch where she has lived for 40 years with her beloved husband. Lorene Lueck had begun the long descent. Mastroeni recognizes the telltale signs: memory loss, delirium and anxiety. Before long, the family has to hire full-time help for Lueck, who can no longer live alone.

“I watched her slowly leave our world,” he says, “and told myself there must be a better way. People should not have to live this way.”

“We live in a world where we want answers, but with Alzheimer’s disease we are left with more questions than answers,” Mastroeni says. He believes that although progress is being made, it just is not fast enough.

Today, Mastroeni is a researcher at ASU’s Biodesign Institute, expected to become one of the world’s largest teams of neuroscientists devoted to combating Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Coloring outside the lines

With the show-stopping headline, "Alzheimer’s study discovers toxic protein behind disease that could radically change treatment research," Newsweek chronicled Mastroeni’s discoveries last year.

Along with ASU chemistry professor Sidney Hecht, director of the Biodesign Center for Bioenergetics, Mastroeni and his team studied whether cell breakdown — not plaque buildup (the prevailing theory) — leads to the development of Alzheimer’s.

With his research partner, Paul Coleman, also part of the ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research team, Mastroeni focuses on an emerging science known as epigenetics. Researchers have long believed that Alzheimer’s is a function of genetics: If you had a certain genetic profile, you would get Alzheimer’s.

Epigenetics refers to the ways in which the world around us modifies how our genes are expressed. Chemical modifications resulting from stress, diet, sleep, exercise or the environment can switch gene behavior from healthy to unhealthy. Some theorize that Alzheimer’s is triggered by the way genes turn on and off in the brain.

Together, Mastroeni and Coleman examine genetic changes within the brain regions affected early in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Their results are shedding light on the genetic basis of how glial cells (cells associated with neurons) go awry, resulting in dementia. Their work could lead to new targeted therapies for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

Mastroeni and Coleman’s work has been supported in part with funding from foundations devoted to combating the disease and to advancing science, including the Alzheimer’s Association and the NOMIS Foundation. Additionally, their work has received support from the Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium, a nonprofit organization composed of seven member institutions, including ASU, and three affiliated medical institutions across the state devoted to Alzheimer’s research.

The long goodbye

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, every 65 seconds someone in the U.S. develops the disease. Among the top 10 causes of death in the United States, Alzheimer’s is the only disease that cannot be prevented, slowed or cured. Some 14 million Americans will be afflicted with the disease by midcentury, at a cost of $1 trillion.

Despite its costs to society, Alzheimer’s receives far less than the research funding dedicated to cancer, also one of the world’s most deadly diseases. In fiscal year 2019 the National Institutes of Health will direct $2.3 billion toward Alzheimer’s research and $6.6 billion toward cancer.

Alzheimer’s robs its victims of their sense of identity, memory, ability to reason, understand and even move. The toll it takes on patients, family and society makes Alzheimer’s a worldwide health crisis.

In Arizona, there is strong incentive to lead. According to the Alzheimer’s Association 2019 Facts and Figures report, the state has the nation’s fastest growth rate for the disease. The number of people living with Alzheimer’s in Arizona is expected to grow 43 percent in the next six years. Yet advances in disease treatments may not keep up with the growing number of cases: There has not been a new Alzheimer’s drug approved in more than a decade, and 99 percent of clinical trials have failed.

Like the larger research world, dementias (of which Alzheimer’s is the most prevalent) continue to be confounding. Newer theories maintain that Alzheimer’s is not a singular disease but — like cancer — many diseases with a multiplicity of origins.

Collaborating with the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, Barrow Neurological Institute, Mayo Clinic and the University of Rochester, Coleman has put a new tool on the table: a blood test that can predict the potential of getting Alzheimer’s in people as young as their early 20s.

“We no longer talk about a cure,” said Coleman. “We talk about early detection. The single biggest obstacle to understanding Alzheimer’s is the fact that it resides in your body long before symptoms appear. By the time we know that someone has Alzheimer’s, it’s too late to do anything about it.”

Coleman’s test does more than simply identify neurodegeneration in general; it identifies the specific type of degenerative brain condition.“If the disease could be identified much earlier – close to its origin – there is hope that perhaps it could be slowed or even halted in its tracks.”— Paul Coleman, ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Team

According to Coleman, “If the disease could be identified much earlier — close to its origin — there is hope that perhaps it could be slowed or even halted in its tracks.” Ideally, doctors would test patients as a normal part of their annual physical. One hypothesis holds that there are existing drugs that, if administered earlier, could slow or arrest the disease.

The caregiver conundrum

A study of 1,200 married couples in rural Utah reported an astounding statistic: Spouses of people with dementia have a 600 percent greater risk of developing dementia themselves. (On average, caregivers in the study had been married for 50 years.) A shared lifestyle and chronic stress, isolation, decreased physical activity and the challenges of eating healthy may all play into the decline.

“Until there’s a cure, there’s care,” says David Coon, a professor and associate dean of research initiatives, support and engagement at the Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation and director of ASU’s new Center for Innovation in Healthy and Resilient Aging.

Coon is on a mission to change the way we experience and perceive aging. “I call it ‘hamster head.’ How do I get you off that wheel so I can change the way you think about aging?” he says.

The center supports interdisciplinary efforts to solve challenges in aging — from the individual level to the policy level — by connecting faculty, students and community partners in biomedical research, clinical studies and behavioral interventions.

Coon became transfixed with the elderly as a teenager, prompted by his close relationship with his grandmother, Mary Louise. As she developed what was then called “hardening of the arteries,” Coon stepped up to be her chauffeur and to help her pay her bills.

“The question of caregiving is becoming increasingly complex,” Coon explains. “This is not the same as the day when your grandparents took care of one another. Today, caregiving requires a tremendous commitment of time and money — something that many cannot access.”

Many caregivers lack access to proven treatments to help alleviate stress and distress. In particular, those in rural areas, those with full-time jobs, or those who are homebound lack the kind of assistance that helps them enhance their emotional well-being and physical health.

To answer the needs of those caregivers, Coon and his colleagues are adapting his evidence-based intervention, CarePRO, a group-based, skill-building program for family caregivers. More than 1,600 caregivers have participated in CarePRO, which received the 2013 Rosalynn Carter Leadership in Caregiving Award from former first lady Rosalynn Carter herself.

This summer, Coon began to widen the program’s reach by embarking on a new project, the Sun Devil Caregiver Academy, a proposed home for interventions like CarePRO, training opportunities for professionals to learn them, and continuing education related to caregiving. An anonymous ASU donor gave almost $75,000 to help launch the academy.

Music and memory

Coon’s Music and Memory focuses on the power of music to evoke positive emotions and ease suffering in those with dementia. With musicians from the Phoenix Symphony, the project is a blend of nursing, music performance, music therapy and behavioral science. According to an interview in ASU Now, the university’s online news publication, the project’s researchers found that residents at two area long-term care facilities who participated in the program exhibited higher levels of positive mood and lower levels of cortisol, the stress hormone.

In the beginning of the project, the musicians performed planned selections, but progressively the music became more improvised and responsive to the residents. From fight songs to hymns to complex classical pieces, the musicians took cues from the residents about what music to play. When someone requested a polka, the performers readily complied.

Coon describes one profoundly moving moment when a couple, hearing “their song,” got up to dance.

Fast-forward to innovation

While Mastroeni keeps a keen focus on bench science, his impatience with answers is leading him in new directions. He has an idea for an “Alzheimer’s app” – sort of a Fitbit™ for patients and caregivers.

Using tools like retina scanning, big-data analytics and artificial intelligence, Mastroeni envisions a wearable two-way communications system that supports the social, behavioral, physical, medical and nutritional needs of dementia patients. Through data mining and predictive analytics, the system will store necessary information and experiences, and provide useful information to caregiver and patient.

For example, the mechanism may detect a bout of agitation in a patient. A signal would go to the caregiver, reminding the caregiver that the last time the patient was agitated, a certain piece of music calmed him. Mastroeni even foresees the ability of the patient’s physician to monitor a patient’s health in real time.

Despite advances, dementia remains frightening, frustrating and perplexing. Researchers at ASU and across the world are undeterred. “We’re gaining on it,” Mastroeni says.

Fuel for the fight

ASU’s multipronged, multidisciplinary approach to dementia research received a wellspring of support last spring when entrepreneur and businessman the late J. Orin Edson and his wife, Charlene, gave a transformative gift to the university that was split evenly between the College of Nursing and Health Innovation — now named for the family — and the Biodesign Institute.

At Biodesign, the gift will fund research to identify causes and cures, including through the Charlene and J. Orin Edson Initiative for Dementia Care and Solutions. In the Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation, it will fund research and programs that lead to better caregiving and quality of life. To elevate nursing care overall and within the field of dementia care, the gift created the Grace Center for Innovation in Nursing Education, named for Charlene’s mother.