Tuberculosis, once better known as consumption for the way its victims wasted away, has a long and deadly history, with estimates indicating it may have killed more people than any other bacterial pathogen.

Consumption played a role in many of our stories of the Old West, but even today — despite $6.6 billion spent for international TB care and prevention efforts — it remains a major risk to human health.

A group of maverick scientists from Arizona, Texas and Washington, D.C., has teamed up to develop the first rapid blood test to diagnose and quantitate the severity of active TB cases.

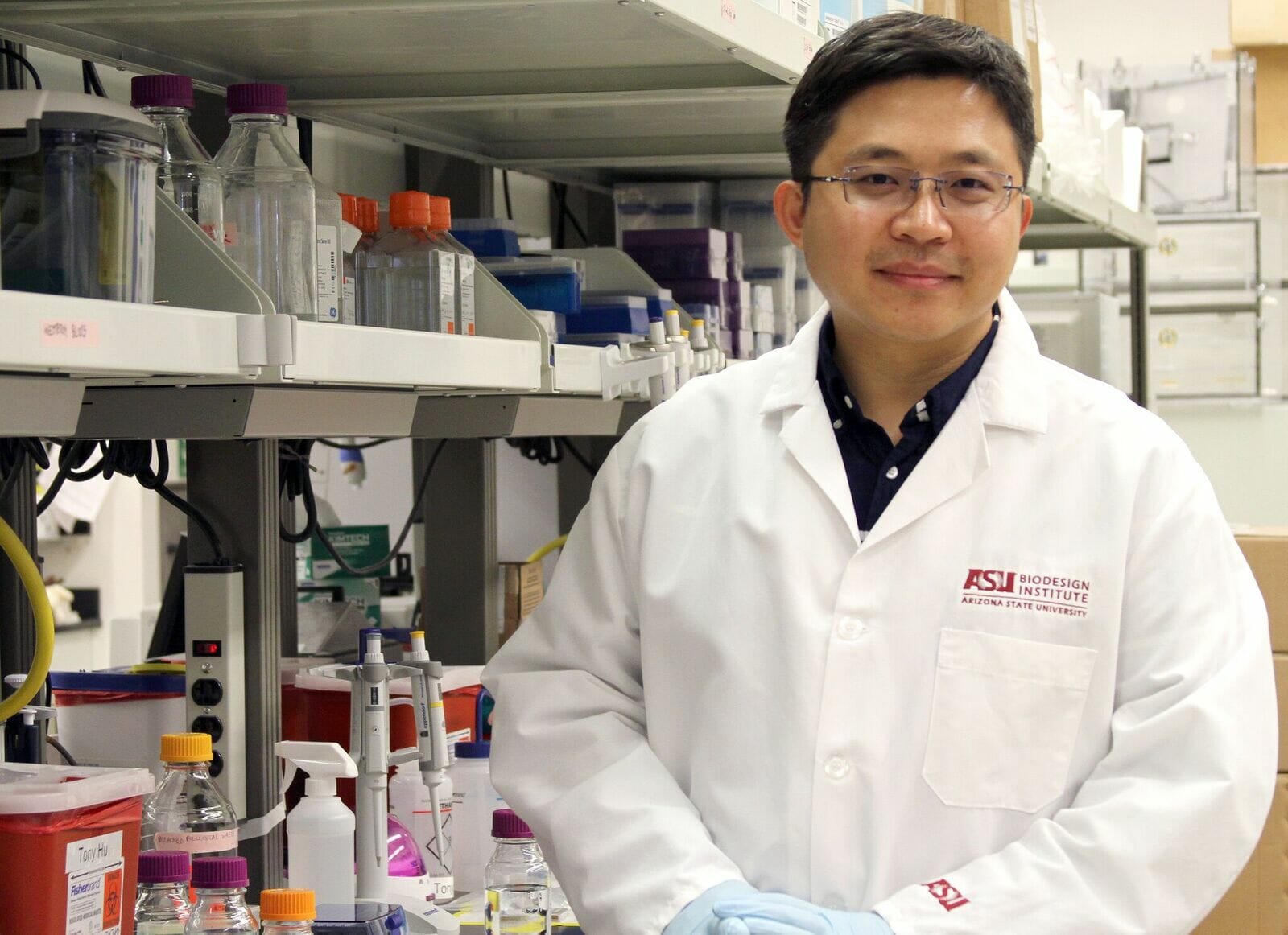

Led by Tony Hu, a researcher at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute, eight research groups, including the Houston Methodist Research Institute and scientists at the National Institutes of Health, are harnessing the new field of nanomedicine to improve worldwide TB control.

“In the current frontlines of TB testing, coughed-up sputum, blood culture tests, invasive lung and lymph biopsies, or spinal taps are the only way to diagnose TB,” said Hu. “The results can give false negatives, and these tests are further constrained because they can take days to weeks to get the results.”

The team’s newly developed blood-based TB test not only outperforms all others on the market but also takes just hours to complete. This is critical since effective TB control requires that patients start treatment as soon as possible to reduce the risk of spreading it.

This test also holds promise for rapid assessment of TB treatment, an important factor in reducing the development and spread of drug-resistant strains.

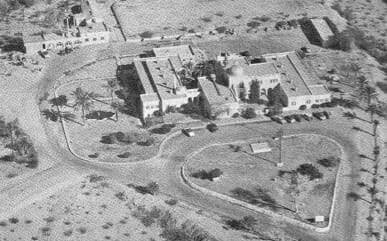

And in a fitting twist of fate, Hu’s laboratory in the Biodesign Institute's Virginia G. Piper Center for Personalized Diagnostics is only about a mile away from the original Arizona State Tuberculosis Sanatorium, a Moorish-influenced structure that opened in Tempe, Arizona in 1934, and had 60 beds available to treat patients.

A history of affliction

Estimates suggest that TB has killed a billion people over the past two centuries.

Locally, TB deeply influenced the early history of Arizona, since the warm, dry climate spurred the growth of sanatoriums and a medical tourism industry that helped give rise to Phoenix’s original population boom in the late 1800s.

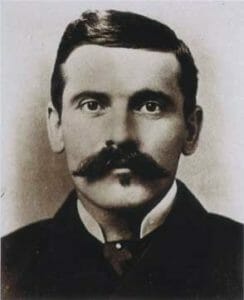

Perhaps the most notorious TB victim in Arizona’s rich history was the Old West's John Henry “Doc” Holliday, a dentist, gambler and gunfighter, whose role at the OK Corral shootout is still re-enacted daily in Tombstone. After the gun smoke cleared, Holliday survived but died just a few years later, finally succumbing to the disease he seems to have contracted a decade earlier.

TB appears to have played a major role in his life, first influencing his migration west for a healthier climate, but also branding him with a prevailing social stigma. In the hit movie “Tombstone,” Doc Holliday’s enemies taunted him by calling him “lunger,” a derogatory term for those afflicted with consumption, who were stigmatized and often removed from society and placed in sanatoriums, such as the one near Hu’s modern-day lab.

Worldwide scourge

Thankfully, TB now has a greatly reduced impact on Arizona, but it remains a major risk, particularly for the developing world and people with HIV infections.

Making matters worse, TB bacteria, such as in Holliday's case, can lurk dormant in a person’s lung tissue, often for decades, before spontaneously producing full-blown TB disease that can then spread to others. Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that up to one-third of the world’s population may have such dormant TB infections.

In 2016, an estimated 10 million people worldwide still develop TB each year, according to the WHO’s most recent report, resulting in almost 2 million deaths. TB treatment has prevented almost 50 million deaths between 2000 and 2015, but TB remains a worldwide epidemic due to the lack of an effective vaccine, the rise in drug-resistant strains and the relatively poor performance of available diagnostics.

A new and easy way to rapidly screen those susceptible to TB infections was recognized by WHO and other public health officials as the major technological hurdle needed to overcome the disease.

Enter Hu and the research team.

Nanomedicine to the rescue

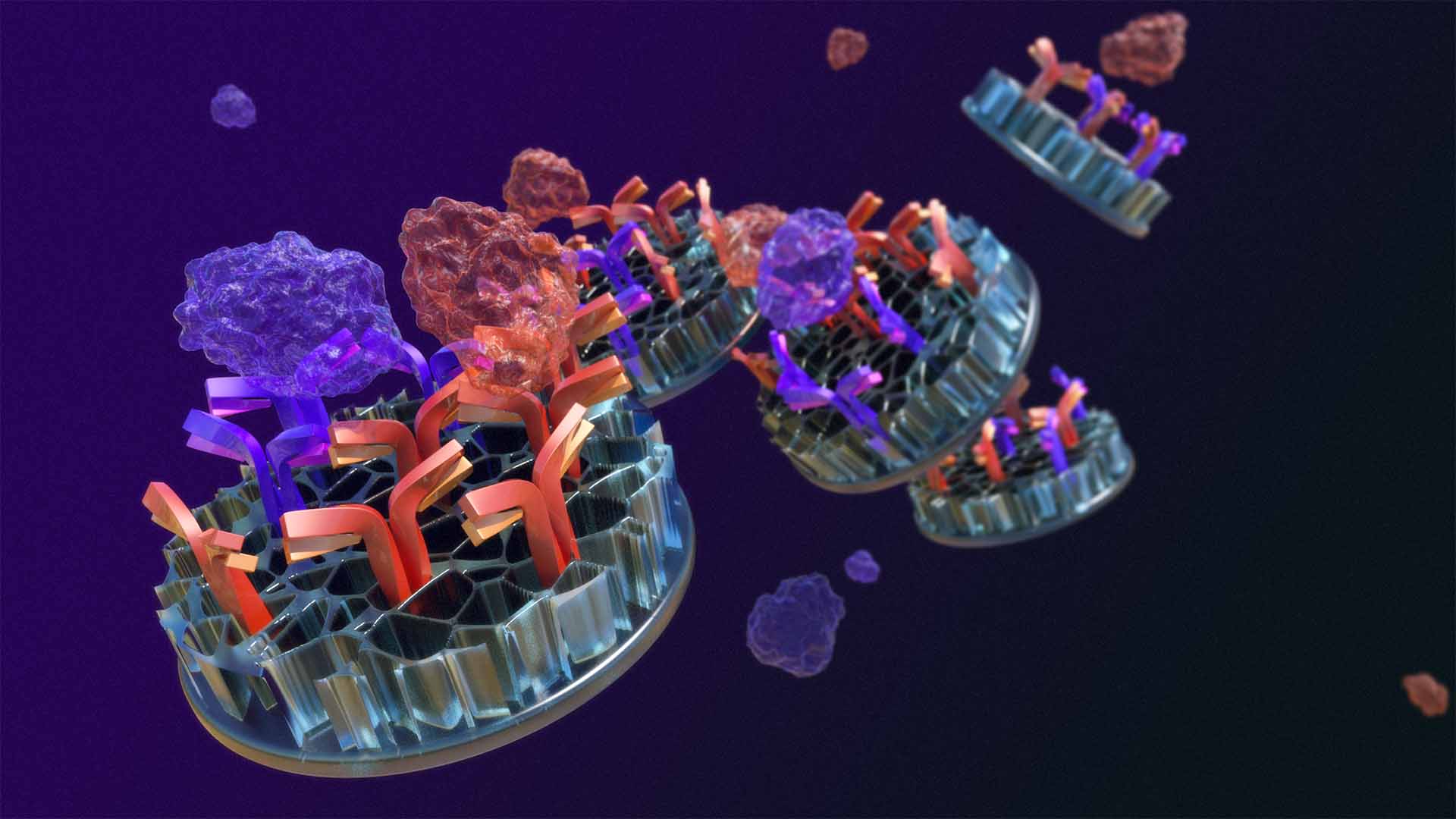

The research team’s newly developed NanoDisk-MS assay (see infographic), could significantly improve TB diagnosis and management because it is the first test that can measure the severity of active TB infections. It does so by accurately detecting minute blood levels of two proteins (CFP-10 and ESAT-6) that TB bacteria release only during active infections.

“We are particularly excited about the ability of our high-throughput assay to provide rapid quantitative results that can be used to monitor treatment effects, which will give physicians the ability to better treat worldwide TB infections,” said Hu. “Furthermore, our technology can be used with standard clinical instruments found in hospitals worldwide.”

Current TB assays often demonstrate reduced performance with HIV-positive TB patients or those with TB infections in non-lung tissues, and these patients can require tissue biopsies for diagnosis. The NanoDisk-MS assay, however, detected lung- and non-lung-resident TB cases with similar sensitivity (about 92 percent) regardless of patient HIV status, and revealed good specificity to distinguish patients with related disease cases (latent TB and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections; 87 and 91 percent, respectively) and healthy subjects (100 percent).

The strategy used to generate this assay may also be adaptable to other infectious diseases. Hu is now developing the current TB assay for clinical approval and hopes to make it available for clinical use as soon as possible to reestablish the role of Arizona and ASU as central players in the fight against TB.

The study, “Quantification of circulating M. tuberculosis antigen peptides allows rapid diagnosis of active disease and treatment monitoring,” was published in the Early Edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

###

Paper Title: Quantification of circulating M. tuberculosis antigen peptides allows rapid diagnosis of active disease and treatment monitoring

Chang Liu1,2, Zhen Zhao3, Jia Fan1,2, Christopher J Lyon1,2, Hung-Jen Wu1, Dobrin Nedelkov4, Adrian M Zelazny3, Kenneth N Olivier5, Lisa H Cazares6, Steven M Holland7, Edward A Graviss8 & Ye Hu1,2*

1Department of Nanomedicine, Houston Methodist Research Institute, Houston, TX 77030, United States

2School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering, Virginia G. Piper Biodesign Center for Personalized Diagnostics, The Biodesign Institute, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85281, United States

3Department of Laboratory Medicine, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, United States

4Molecular Biomarkers Laboratory, The Biodesign Institute, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85281, United States

5Cardiovascular Pulmonary Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, United States

6Molecular and Translational Sciences, U.S. Army Medical Research institute of infectious Disease, Frederick, MD 21702, United States2

7Laboratory of Clinical Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD 20892, United States

8Department of Pathology and Genomic Medicine, Houston Methodist Research Institute, Houston, TX 77030, United States

*To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected]